Ashtanga Yoga

It is not easy to outline the history of Ashtanga Yoga exactly as there is a lack of supporting evidence for the stories that are said around this system of Yoga. However, I believe that the functionality of the system talks for itself. To have a better understanding on Ashtanga Yoga, let’s have a look at where it is rooted, what the practice entails and the benefits of the practice to which it can thank its popularity.

The History of Ashtanga Yoga

If we are attempting to trace the starting point of Ashtanga Yoga back in history, we must look at the lineage of it. Investigating the recent past is easy, as we have many evidence we can use to trace the practice all the way back to Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (born in 1888, in Mysore Kingdom). He is considered to be the father of Western Yoga. His teacher was Yogeshwara Ramamohana Brahmachari, who was told to live in the mountains beyond Nepal (and was the master of 7000 asanas as stories say).

In 1915 Krishnamacharya travelled to Sri Brahmachari's school, supposedly to a cave at the foot of Mount Kailash, where the master lived with his wife and three children. It is said that Krishnamacharya spent seven and a half years studying the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, learning asanas, pranayama, and studying the therapeutic aspects of yoga.

The rumour has it that the foundations of Ashtanga Yoga were outlined in the Yoga Korunta, a 5000 year old text on Yoga, written in Sanskrit by Vamana Rishi, a sage who has brought the knowledge of Ashtanga Yoga back to us. Legend has it that Vamana Rishi was a sage born at a time when Ashtanga Yoga had been nearly forgotten, and as such he incarnated himself deliberately for the task of bringing it back to mankind. So he decided to manifest himself to Earth, but while in the womb he realised that once he comes to birth he will have no knowledge on Ashtanga Yoga, so Vamana Rishi meditated on Vishnu, and it is said that Vishnu taught Vamana Rishi the entire systems of Ashtanga Yoga while in the womb. Vamana Rishi refused to be born until they had covered the whole curriculum. It is said that the pregnancy was long and troublesome. Once born, he then noted down the Yoga Korunta.

Is Ashtanga Yoga truly rooted in the

Yoga Korunta?

Krishnamacharya was said to be able to find the remains of this text when he visited the Library of Calcutta in the years of 1922 and 1924 and claimed that the text has outlined the entire system of Brahmachari’s teachings. And although he had a copy of the text written on banana leaves, he mishandled it and the text was eaten by ants. Therefore there is no evidence whether the system was actually outlined in the Yoga Korunta or not.

However the question where the practice is rooted should not change the effect of it. Once one begins to practice with dedication, one will feel how it helps to heal. I like how Pattabhi Jois describes the importance of the history of Ashtanga Yoga:

“Look, I’m just teaching what I learned from my teacher. Krishnamacharya taught me this, this is what I’m teaching you; I say, does it truly matter if this method of yoga is five thousand years old or five years old?”

“Vina vinyasa yogena asanadin na karayet -

Oh yogi, do not do asana without vinyasa”

The book, Guruji: A Portrait of Sri K. Pattabhi Jois Through the Eyes of His Students (Guy Donahae, Eddie Stern) says “The true test of any system of yoga is, does it work? Does it help you in life? If it doesn’t, do something else! Life is too short. If it is helping you, then carry on doing it. If not, there are many systems of yoga to choose from. So I believe PattabHi Jois is teaching what he learned from his teacher. Where did Krishnamacharya learn it? Did it come from leaves? Did it come from the Gurkhas in Northern India? Was it just for gymnastic teenage boys? I’ve heard different theory and philosophy about it. None of it matters. If you practice it and you feel better when you do it, do it again the next day.”

But what is the system of Asthanga Vinyasa Yoga?

““At the heart of Ashtanga is Vinyasa. The essence of Vinyasa is the synchronicity of breath and movement.” ”

Let’s begin with the etymology of the word:

ashtao - eight

anga - limb

Ashtanga Yoga therefore is the eight limbed yoga as set out in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. Let’s have a look into different ancient texts and how the eight limbed path appears in them. Although my attempt was to put them into chronological order, it’s important to mention that we don’t clearly know the precise time of their formation.

6000 BC - 4000 BC — Vedas

The oldest Sanskrit scriptures are the Vedas, a large body of religious texts originated in ancient India describe yoga in the Yoga Tattva Upanishad: “Now hear Hatha-Yoga. This yoga is said to possess eight subservients, yama (forbearance), niyama (religious observance), asana (posture), pranayama (suppression of breath), pratyahara (subjugation of the senses), dharana (concentration), dhayana (contemplation in the middle of the eyebrows) and samadhi, that is the state of equality.” It is one of the oldest recordings on what yoga is, and we can already see the system outlined.

1000 BC - 500 BC (approximately) — The Bhagavad Gita

If we are looking at the description in The Bhagavad Gita we find that there are 4 kinds of yoga that are mentioned. All four kinds have one purpose: union with God. The word yoga is rooted in yuk “to unite”. It is the realisation of the unity of all life; a path or discipline which leads to such a state of total integration or unity.

The 4 kinds of yoga as described in the Bhagavad Gita are:

Jnana Yoga (yoga of knowledge)

Bhakti Yoga (selfless service)

Karma Yoga (yoga of action) and

Raja Yoga (the royal path)

Raja yoga is also said to be a synonym for Astanga Yoga. However, there are no asanas mentioned in The Bhagavad Gita whatsoever.

500 BC - 400 AD (but some date it even earlier) — The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

Further defining yoga, when looking at The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali we find in Sutra 1.2:

“The restraint of the modification of the mind-stuff is Yoga. If you can control the rising of the mind into ripples, you will experience Yoga.”

In Patanjali’s sutras the 8 limbs are clearly outlined, however, he does not give any specific instructions on asanas (postures). Asana is only mentioned as “Sthira sukhamasanam” (Asana is a steady, comfortable posturer.) The reason for that could be that back at that time people needed not complicated asanas to be practiced as the body was in a healthy condition for meditation, or that the knowledge was taught orally and no transcription of them were needed.

10th - 11th century (some say even 13th century) — The Yoga Yajnavalkya

The Yoga Yajnavalkya says in verses 43-45: “Understand that enlightenment is yoga (yoga is enlightenment), and yoga has eight limbs. Yoga is said to be the union of individual self and the supreme self.” (This can be understood as the union of Atman and Brahman, or the individual consciousness and the collective consciousness.) The Yoga Yajnavalkya sets out 8 asanas in 2 groups: asanas for contemplative practices and asanas for cleansing the body.

15th century — The Hatha Yoga Pradipika

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika describes yoga as “State of union between two opposite poles, that is to say Shiva and Shakti, body and mind, individual and universal awareness; process of uniting opposing forces in the body and mind in order to realise the spiritual essence of being.” The Hatha Yoga Pradipika mentions 84 asanas of which only discusses 15 asanas in details. This could be for the same reason as not mentioning how to do asanas in the sutras. Possibly the practitioners were in possession of that knowledge or were taught orally.

As you can see, the system of 8 limbs and the definition of yoga is mentioned in all these texts. However the asana system of the Asthanga Vinyasa Yoga is not mentioned at all, yet alone the way it was taught by Krishnamacharya and his later students. What’s important to note is that the asanas are just one aspect of yoga. Yoga is not limited to postures performed on a mat, but it is the way to live life, or dare I say, yoga is life.

The 8 limbs are:

Yamas - universal codes of conduct

Niyamas - personal codes of conduct

Asana - postures

Pranayama - vital energy control

Pratyahara - withdrawal of senses

Dharana - concentration

Dhayana - meditation

Samadhi - union with or absorption into ultimate reality

Each limbs are meant to be practiced simultaneously. Although there are different opinions and understanding on the ways of practice. In an orthodox practice one does not do pranayama before the second asana series, so I was told when I entered a shala that follows Sharat Jois’ teachings (grandson of Patthabi Jois, official lineage holder of Ashtanga Yoga). Whereas the students of Manju Jois (son of Patthabi Jois) seem a little bit more flexible on the practices of Ashtanga Yoga.

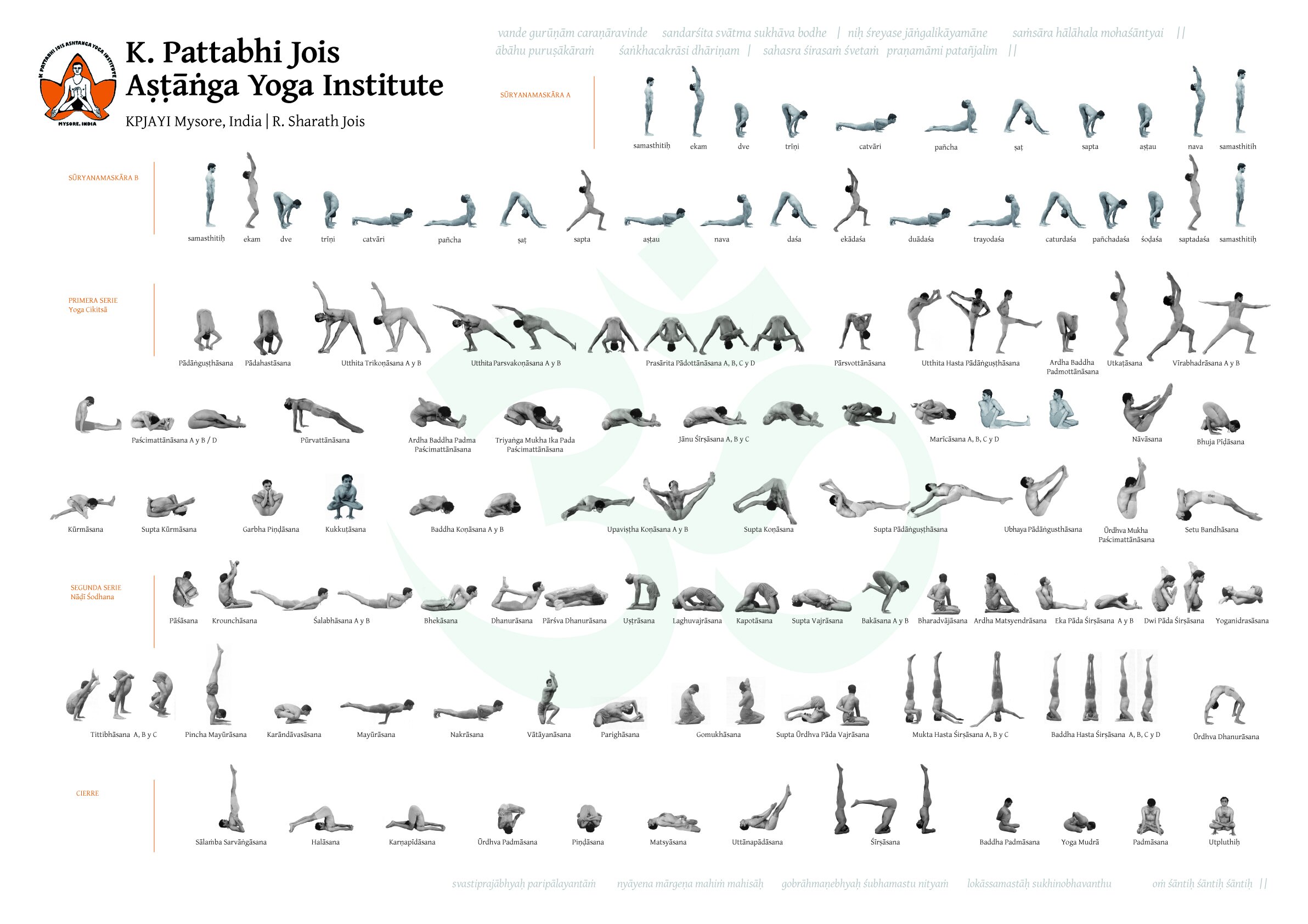

The Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga system has 6 series of asanas to practice. They are:

Primary Series - Yoga Cikitsa - Yoga Therapy

Intermediate Series - Nadi Shodana - Nerve Cleansing

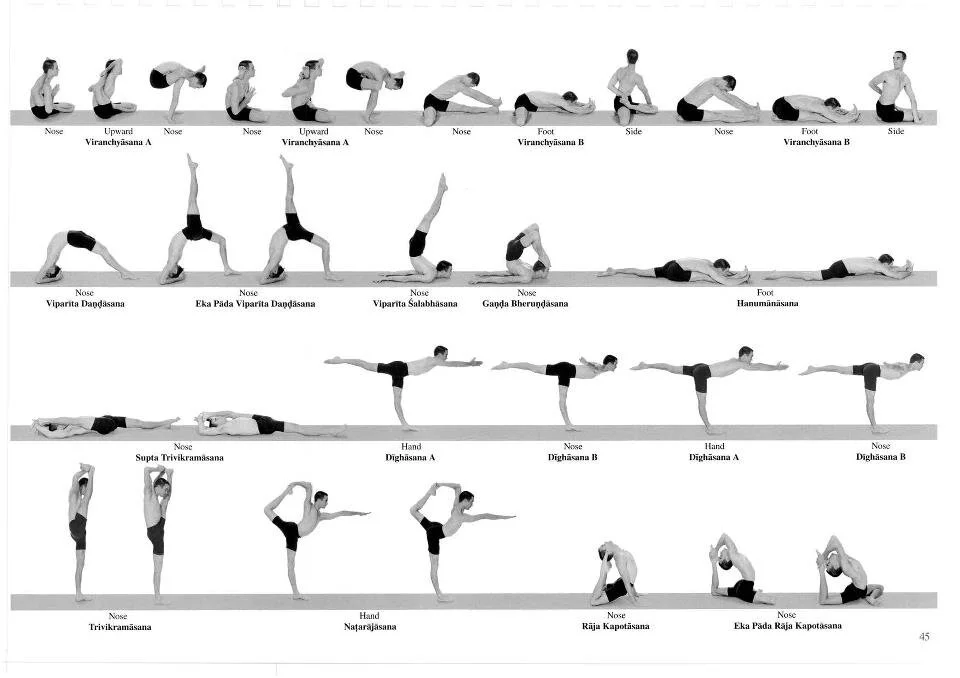

Advanced Series (A, B, C, D) - Sthira Bhaga - Sublime Serenity

While the names indicate that the first series is easier than the advanced one, that could not be further from the truth. The primary series takes years to master and holds great challenges for everyone. The rest will gradually unfold from there, but one should have a teacher to work with who can give advice on when the student is ready to receive a more advanced posture. Most students begin with a half primary practice that has modifications for the poses if needed and build up from there. While the 8 limbs of Ashtanga Yoga should be practice simultaneously, the postures and series meant to be practiced in a sequence, leading up to more advanced postures (also called a vinyasa krama method, intelligent sequence of postures, where one starts from the easier asanas and through thorough preparation the practice leads to more advanced asanas).

When practicing postures on the mat, it is not only the movements that are outlined. From the exterior, looking at a yogi/yogini practicing, there is only so much the eyes can tell us about the practice. Even when practicing asanas, the breath and the gaze is controlled.

Tristana (the three pillars) is the foundation of Asthanga Vinyasa Yoga, helping the practitioner to cultivate the ultimate presence of mind, focus and stability. The three pillars are ujjayi breath (victorious breath), bandhas (energy locks that help you align the body) and drishti (yogic gaze). Through the regulation of the breath and focus of the mind, the asana practice transforms from a simple bodily exercise to a total mind-body experience, resulting in a practice with a meditative quality.

I highly emphasise the importance of the breath to my students. Reason being is that we live in the time when the visual reference of achieving something is overpowering the real experience itself. I feel that in this new age, conditioned in the society that we live in, the “way we look” seems to be more important than how we feel, when in reality both should be at least equally important. In yoga, once the practitioner establishes a close relationship with the breath, he\she will be able to use that as a guide. Not only to establish the rhythm of the practice, but to receive feedback from the body through the nervous system that is directly linked to the breath. Only then we can work with the deeply embedded patterns of our minds. We can push ourselves into a posture and look a certain way, but that is not a clear indication that we are firmly grounded and have found a steadiness in a posture. This of course doesn’t mean that while working out of our comfort zone we will not experience effort in the breath. Our job is to learn what is the right amount of effort needed for overcoming the obstacles while recognising when too much of that effort strains the breath. Such practice may not only not serve the practitioners but could also lead to injuries.

And lastly on the importance of drishti (gaze). Resting the gaze on one of the outlined 9 points in the practice improves the concentration of the practitioner. It also helps to turn the awareness inward when joining a Mysore-style class (where the practice is led by the pace of your own breath following the sequence) and not become distracted by others and events around you. In my personal opinion drishti can also add an extra challenge to the balance. It then requires the practitioner to utilise pranayama and the vayus to fully be present in the body.

I hope this article helped you to understand the history and system of Ashtanga Yoga. The benefits of following such practice ranges from physical fitness and mental well-being all the way to a deeper spiritual experience, if one wants to use the system that way. But as I like to say to students who ask me about the benefits of practicing Ashtanga Yoga, you get out what you put in. And that entirely depends on the student’s attitude and focus. I consider Ashtanga Yoga as a tool to achieve anything we want. But in order to do that, the tool must be used consistently with discipline and consideration. As Sri K. Pattabhi Jois said: yoga is 99% practice and 1% theory.